STORIES

Balloons

By Skyler Slade

When Grooveshark Lite launched on April 15, 2008, it was a near instant success for the company. After months of anemic signups for our beta Peer-to-Peer paid download site, “Lite,” as we called it, gave us the shot in the arm we needed to stay alive. We soon crossed the 50,000 registered users threshold, putting us back in good graces with one of our biggest investors, who required that we achieve this milestone or else they wouldn’t invest any additional money in the company. The understanding at the time was that without this kind of user growth and additional investment, we wouldn’t survive.

As far as I know, before Grooveshark Lite, there wasn’t any place on the web dedicated to music where you could listen to any song, whenever you wanted, for free. There were music videos on YouTube, but the catalog was limited and at the time, the video-focused site didn’t have the features that you’d expect from a music service (shuffle, repeat, easy playlist management, and so on). The iTunes Music Store offered free 30-second previews of songs and there was Pandora for online radio, but the service imposed lots of restrictions on how you could use it, like limiting the number of times you could click the skip button. Spotify didn’t exist and wouldn’t be available in the US for several more years; Apple Music, Rdio, Google Play Music and all the rest didn’t exist either. Lite was really the first of its kind.

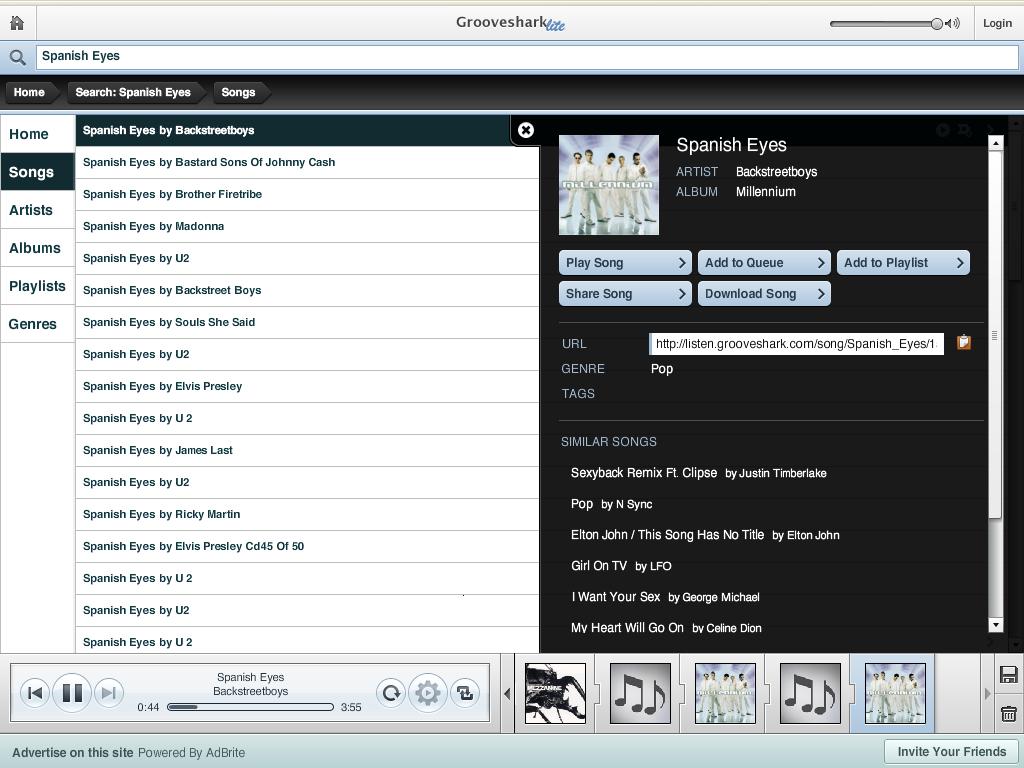

Lite was written in Adobe Flex, a framework which ran on Adobe Flash. This was before HTML 5 and the modern web and Flash was the only platform available for building a cross-platform, media-rich, interactive web app. Lite took full advantage of this interactivity: as you browsed the service, lists of songs, artists, and albums animated in and out of view, just like an iPod. As each new song played, it slid into view, and the interlocked puzzle piece of album art updated, highlighted in blue. Lite was beautiful to look at and immensely fun to use.

Grooveshark Lite soon after its launch

To actually deliver music to the application running in the browser, we used an open source implementation of Adobe’s Real Time Streaming Protocol (RTSP) server. Lite would retrieve search results, album listings, playlists, and other music catalog data from our web servers, using the SOAP messaging protocol, and music would stream from another set of servers using RTSP.

Soon after Lite’s launch, someone on the team created an internal web page which would show the current number of active music streams on the site along with other statistics about the growth of the service. To determine the number of active streams, Travis created a script which would connect to each RTSP server and run commands that would count the number of open connections. The number of open connections indicated the number of active music streams. We connected a computer to a projector and displayed Lite’s stats page on the west wall of the office for everyone to see.

Soon after the page’s premiere, someone else modified it to add JavaScript which would animate multi-colored, falling balloons each time we hit a new record of active streams. At first, the balloons fell once or twice a day. Then several times per day, then once every hour, as more and more people discovered Lite and listened to more songs. A tradition soon developed of applauding each time the balloons fell: every time we hit a new active streams milestone the entire office erupted in celebration. This continued for weeks.

After some time, everyone got used to breaking new records every day and we either turned off the projector or used it to show something else. Travis would later discover that his script regularly miscounted streams because the RTSP server held open its connections for some time after they’d stopped being used for streams. This meant that many of the records we thought we’d broken, we hadn’t actually broken at all, or at least not when we thought we did. Fortunately, other, more reliable stats told the story better anyway. Both registered and anonymous users were way up and daily, total stream counts were up too. The company had escaped yet another existential threat.